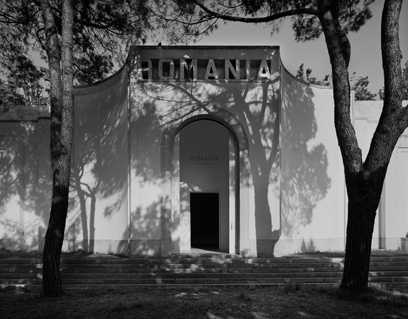

ROMANIAN PAVILION 1932

BRENNO DEL GIUDICE

THE MYTH OF PLACE

BOGDAN GHIU

Sometimes we arrive in a place (what is a place?) and we can’t tear ourselves away from it. But more often than not there is nothing special about this kind of space that we might call place.

A place is always constructed from the exterior. A place is a situation. A place is a garden. A place is an aerial, invisible labyrinth. A place is a common space, which not only belongs to people and is for people, but also opens you up to unexpected, vaster, cosmic communities. Place is that which eludes space: an architectonic drama created by an architectural decision.

Such a place, too, is the Romanian Pavilion in the Giardini di Castello. In fact, the entire architectural sub-ensemble of which it is part. In fact, the entire space that this ensemble circumscribes. The whole of this ad-hoc community awakens to life through construction, under the uncontrolled and uncontrollable impulse of architecture, of man’s urge to build.

Between two doors, between two worlds. Enter the Romanian Pavilion and try to pass through it, to the other side, to cross this apparently terminal, limited space. It is a masked boundary. The enchantment of places is always, in fact, political. Architecture is always a political opus, a power construct.

The Romanian Pavilion in the Giardini di Castello conceals an exit. And an entrance. It is built to mark and at the same time to mask an opening, a passage to the other side and an opportunity to invade, infiltrate, betray. The main entrance, a genuine triumphal arch, which, given its verticality, might figure the famous “Gate of the Law” described by Kafka, in fact conceals a fracture, a fissure in the construction of the real.

I shall attempt to tell you the story of this place, for each place is a story, albeit not one that is narrative, historical, literary, but an architectonic story, a story that is a structure of resistance and a node of tensions.

In 1932, in the space of the Venice Biennale (which embodied the World itself, i.e., the “civilized world”), there was no place for new nations, for new allies (for the purpose of creating a new “New World”) such as Romania, for example. And so recourse was made to the political power of architecture; the Architect was summoned (in this particular case, Brenno del Giudice). And the Architect stepped into a complete paradox: He created a late, additional, surplus Utopia, a new world on a strip of island. A kind of America.

What the Architect, Architecture, did was cross the River (Rio dei Giardini) and annex a portion of space from the Isola di Sant’Elena. From the historical point of view, we find ourselves in the midst of expansionism and imperialist annexation. New nations, solely in their capacity as nations, are either annihilated or subjugated or co-opted. Power is an architecture.

And so, like in a myth, the architect crosses the River, builds a Bridge, constructs an ideal, ordered, architectural space on the other side, on the Island: the Garden, Utopia—the Garden of Utopia. And at its terminus, the Wall. Architecture is the Myth in itself, in action, a construct of bridges and gardens. Every architectural act constructs, both consciously and unconsciously (the same as every political decision), Utopia; it creates a Myth, releases the structuring, creative forces of the Myth.

The story, the founding myth of the Place of which the Romanian Pavilion is also part, unfolds in three tempos, in three acts, in three dramatic situations. In the first act, the architect gives free rein to a contradiction: He constructs an ample, harmonious perspective, he celebrates an opening but then immediately closes it, blocks it off, inverts it, contradicts it. The so-called Pavilion of Venice, of which the Romanian Pavilion is also part, is a broken perspective, twisted at a 90-degree angle, transformed into its opposite, which is to say, into a Wall, a boundary, a barrier, a dam holding back the Exterior. The first contradiction, the first tension.

But the Exterior, thereby repressed, concealed, excluded, created, and consolidated, returns to take its spiritual revenge in the virtual space of impersonal affects: The entire intermediary space becomes a hidden garden, a secret garden. And it is precisely the invisible battle between the Exterior masked, blocked by the political Wall of architecture, that indirectly, involuntarily, uncontrollably, unconsciously constructs, generates, structures this space as a Place of transit. The row of pavilions, of which the Romanian Pavilion is also part, wants to conceal the rest of the world, to consign the Exterior to oblivion, but the Exterior takes its revenge, returning by discreet ways and at the same time referring to something else. Like an enchantment.

Without the architect (architecture) wishing it, but precisely as a result of his decisions and actions, what is created is a tense, intermediary, pneumatic space. The attempt to forget, obturate, mask the world, the Exterior, creates an agonal, di-agonal space, a space of disputation, of negotiation, which draws us in and holds us prisoners, without our realizing it, precisely because of its founding, structuring tensions, its non-spatial or supra-spatial, archi-spatial architectonics, indirectly generated by architecture.

The architect, architecture, has passed through, building a bridge, over the Rio dei Giardini like over the Lethe: a river of forgetting, beyond which he builds a Dream, the political dream of architecture itself, as a decision that bisects the world, that opens perspectives only to obturate them, rotating them, perpendicularly, along the horizontal, transforming them into their opposite.

This is the Tragedy, the founding mythic tension of this Place.

The blockage of the Exterior transforms this Place into an intermediary space, into a room, into a storeroom, into a secret garden, into an interior, purely spiritual labyrinth. We can’t even imagine what a drama we are experiencing here: an archi-tectonic drama, the drama of the political, politico-architectural birth of space itself. This Place tells us the story of the very birth of Space qua the birth of the World. It is this story, this Fable, which we each experience individually.

And years later comes the third act of the drama, of the myth of this place: the disruptive intervention of the South, the building in 1964 of the Brazilian Pavilion precisely along the axis of the short perspective of the ensemble created by architect del Giudice, arriving to spoil the short-range Europocentrist triumphalism of this micro-utopia, this microharmony.

With its lateral transparency, the Brazilian Pavilion in fact rebalances the political intention to close off the place; it thwarts the plan to conquer, by closing, separating and segregating the world. Long live the South, the avenging Exterior!

The world cannot be closed, blocked off. The Romanian Pavilion is the last, at the end of the row. Which is to say, at the margin, on the un-natural, constructed, political boundary of the civilized, architectural world, the World-Space. Likewise, Romania today is at the terminus of the European Union, a frontier of this agitated conglomerate: a frontier-country, a wall-nation. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the countries themselves became Walls.

But the rôle of the peripheries, frontiers, and intermediary buffer zones is ambiguous, porous, permeable, ambidirectional. In the Romanian Pavilion, corresponding to the bridge that del Giudice built over the little Rio dei Giardini, there is a hidden “service access,” through which it is possible to cross to the other side, emerging once more into the real world outside from architecture’s utopian garden, but through which the world beyond, the constructs and utopias of political architectures can penetrate, illegally infiltrate, smuggle themselves into the civilized/built world.

Peripheries act as intermediary places between “world” and “non-world”; their rôle is to open secret doors into the depths of hidden gardens.

Cross the Romanian Pavilion in both directions. Try to enter, to exit, and to re-enter through both its Gates, the large, triumphal Gate (of the “Law”), and the small “service access” (the Gate of “Lawlessness”), taste the forgotten delights of the always illegal, suspect crossing of the borders that continue to define, architecturally and archetypically, the World, Space itself !