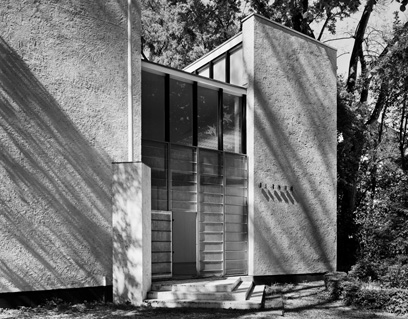

DUTCH PAVILION 1953

GERRIT RIETVELD

NORTHERN LIGHT

HERMAN HERTZBERGER

“Common Ground” is a space or place where people convene and interact with one another in some way, either planned or spontaneously, so that something shared arises or will arise. It is all about spatial forms that are organized in such a way that they provide opportunity and impulses for social contact. They are spaces that enhance the chances of an encounter and work as catalysts in terms of see-and-be-seen; they contribute to an expression of what people have to do with one another. We have previously referred to that as “social space” and regard it as characteristic of the city: inviting and binding.

The Giardini form an island in the city where the beau monde of the international world of art and architecture attempt to impress one another with their biennial crop of art and architecture in their national pieds-à-terre set up as cultural country homes. Within each bastion you feel yourself a guest on national soil, although only a few pavilions genuinely succeed in expressing, by means of their spatial design, something of the national character of the country they are representing. In that respect, the pavilion that Gerrit Rietveld designed in 1953 is unmistakably Dutch, with characteristics of the Dutch mentality we are proud to share with the world, and of which, 60 years on, Rietveld still appears to be a marvelously good exponent. His light-footed and straightforward use of material, composed to form a lucid and well-organized space without needless trappings that evokes associations with sobriety and propriety, harmonizes well with the image that the Netherlands attempts to radiate. The building conceals nothing, reveals itself completely, opens itself entirely inward and outward. Inside, you enter the unmistakable northern air, where the freshness and clarity of the minimalist Mondrian squares originated, and which is invariably associated with polders, dikes, and milk-white. The light is also northern, entering via rising gable-fronted “dormers,” or rather roof compartments, and acquiring its lucidity from its filtration through horizontal ceiling louver components. But the most surprising element is that the incidence of light changes throughout the day, due to the fact that the roof compartments receive light from different directions, illuminating the various corners of the building as the day wears on.

The pavilion actually consists of a single square space, comprehensible at a glance, articulated in four alcove-like bays that correspond to the roof compartments and follow one another in windmill-sail formation. Besides the storey-high glass fronts between the bays, all the walls are available as exhibition space; artists could wish for no more, at least at first sight.

The only slightly negative point is that the ceiling, in one single surface, does not reflect the articulation of the floor plan. It would have been more in line with the plan of lucid expression if the bays that allow the incidence of light had remained spatially visible over their full height. After all, in Rietveld’s work in general, inside and outside are not separate worlds. On this occasion, the interior does not provide what you read on—and therefore expect from—the exterior.

Rietveld designed this pavilion as a small-scale museum, with the apparent intention and anticipation of providing the best conditions for the work that Dutch artists would display, in the presumption that they would accept and appreciate the space as it had been conceived with the intention to do full justice to their work. But real-life practice decreed otherwise. Time and again, people have been zealously engaged in transforming the building into a completely new space, an artwork in itself, in order to make it a component of another idea. In this process, the lucidity of the original design has been repeatedly engulfed by a new identity. This being the case, it is one of the building’s qualities that it has invariably lent itself to amendment back to its original state, although it is doubtful if Rietveld had foreseen such rigorous use of his concept. He could only expect what he could imagine and probably could not anticipate that the space as a whole would increasingly become a part of the world of ideas in which art and architecture would participate, with the ultimate consequence being the possibility of a black box: optimally compliant and without the necessity of an architect who determines an identity. After all, the identity of the building is consistently changing. You may also wonder about the extent to which the Netherlands still has an own national story to tell, like all those other countries with their own pavilions, and whether or not that sense of nationality still signifies anything. But as common ground it remains excellent accommodation in the open-air museum into which the Giardini are transformed during the Biennial.

The pavilion that Rietveld contributed as a mini-colony of the Netherlands to the international community of cultural pieds-à-terre continues to shine, independent of national intentions, due to its whiteness and lucidity and as a legacy and memory of an era in which architecture managed to exude optimism. It is thus a distant scion of the internationally shared style of white cube-like buildings.