CANADIAN PAVILION 1958

BBPR, GIAN LUIGI BANFI, LUDOVICO BARBIANO DI BELGIOJOSO,

ENRICO PERESSUTTI, ERNESTO NATHAN ROGERS

REMOTELY SENSING THE PLACE

DINU BUMBARU

(…) parmy d’icelles champaignes est situee la ville de Hochelaga, pres & joignant une montaigne qui est à lentour d’icelle, labourée & fort fertile: de dessus laquelle on veoit fort loing. Nous nommasmes la dicte montaigne le mont Royal. La dicte ville est toute ronde, & close de boys à trois rencqs, en facon d’une piramide, croisée par le hault (…) il y a dedans icelle ville, environ cinquante maisons longues d’environ cinquante pas ou plus chascune, & douze ou quinze pas de larges, & toutes faictes de boys couvertes & garnyes de grandes escorces & pelleures desdictz boys aussy large que tables, bien cousus artificiellement selon leur mode (…) Et au meilleu d’icelles maisons y a une grande place par terre ou font leur feu, y vivent en communaulté, (…)— Jacques Cartier, second voyage

In 1535, the French navigator Jacques Cartier visited the round fortified city of Hochelaga where Iroquoian people lived a communal life in longhouses built of wood, set in an iconic landscape of fertile fields at the foot of the hill which he named Mont Royal. The publication of Cartier’s travels and detailed descriptions of Hochelaga’s architecture in France and Italy gave these places a written existence and invented modern day Montréal on European maps. Today, scholars and archaeologists still debate the actual location of ancient Hochelaga or the original name of the mountain, yet Montréal grew from a mystic experiment founded in 1642 to the cradle of the industrial revolution in Canada, one of the main North American gateways for immigration and trade, and now an international university metropolis designated City of Design by UNESCO.

Perhaps the most Canadian of Canadian cities, Montréal is the largest of a 325-island archipelago in the mighty St. Lawrence River, far from the ocean but closer to Europe than New York by ship. Founded on a French cultural and cadastral layout, its modern construct rests on an ongoing spirit of endeavour, métissage, and exploration. In the past, it was a place of smokestacks, factories, and the grain elevators concerned with imperial trade and accommodating rapid demographic growth in a context of strong social inequities. Now it is a place of aeronautics, computer imagery, and festivals devoted to local heritage, global environment, citizen participation, and innovation toward urban livability. Despite its urban compactness, which contrasts with the country’s immensity and many of its cityscapes, Montréal’s architecture of triplexes and continuous streetscapes of exterior staircases results in the same dynamic and complex interchange between cultures at the heart of a shared sense of place in Canada and in Canadian cities.

In 1958, the year the Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was completed, Canada was in a confident mode—in less than 10 years, it would be host to the whole world in Montréal at a celebration of the centennial of confederation at Expo 67, with an outstanding feast of architecture and hope for a brighter future.

The pavilion is the work of the Milanese architect firm BBPR and its founding partner Enrico Peressutti. Founded in 1932, BBPR was active in the debate on the modernization of architecture in Italy and engaged in the resistance. After the war, it was commissioned to design memorials to Italian victims of concentration camps and to restore damaged landmarks and design new structures, including a number of exhibition spaces and structures such as the American Pavilion for the 1951 Milan Triennale. Among BBPR’s most noted buildings is the residential Torre Velasca, completed in 1958, whose design introduces some considerations for context.

Architect Arthur Erickson has said:

Architecture, as I see it, is the art of composing spaces, in response to existing environmental and urbanistic conditions, to answer a client’s needs. In this way the building becomes the resolution between its inner being and the outer conditions imposed upon it. It is never solitary but is part of its setting and thus must blend in a timeless way with its surroundings yet show its own fresh presence. (www.arthurerickson.com)

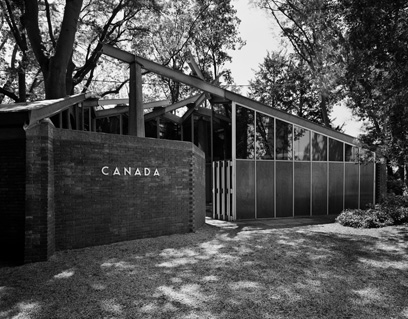

Addressing the site with dignity and relevance is one of the most fundamental acts in the process of architecture. The Canadian Pavilion is situated on a low hill in the southern corner of the Giardini, right between the British and German pavilions, two neighbours qualified by a strongly frontal and axial symmetry and solid volumes of classicist inspiration. In contrast, the Canadian Pavilion is shaped as an asymmetrical polygonal enclosure gravitating around a pillar, which acts as the building’s vertical axis and anchor, its own axis mundi. The top of that pillar is the source—or maybe is it the climax?—of a spiraling sequence of steel beams resting on each other and on the perimeter wall, partly exposed over the exterior patio and partly supporting a faceted roof over the interior space. The building is shaped around the old trees—living monuments of nature treated as artifacts, or columns holding the foliage vault over the pavilion?

As with any architecture, the pavilion results from intents, constraints, and process. How was the dialogue between BBPR in Milan and the Canadian client? Was there a conscious Canadian intent? Yet, from afar, even without such knowledge, the pavilion’s complex assemblage of forms and its use of Canadian materials, such as the Douglas fir paneling or, more poetically, the “sky above between the tree foliage,” offer an evocative hybrid between the First Nations’ movable houses and the brickscapes of cities and industries seamlessly connected to the gardens in a way that’s distinctive yet respectful of the neighbours.

Somehow, the pavilion illustrates Canada’s permanent challenges for architecture—providing meaningful shelter in harsh conditions; creating presence on the land within a layered landscape of ancient and recent cultural patterns, memories, and aspirations; keeping social recognition for authenticity in a world of globalized icons and often powerful neighbours. As longhouses provided Jacques Cartier an insight on Hochelaga, the new houses of young Canadian architects at the 13th Biennale will hint at a Canadian sense of place and of being, beyond the image of wilderness. As Cartier gave a new name to the mountain and somehow invented Montréal on maps, the constantly renewed experience of the pavilion and its glazed-in trees reinvent and perpetuate the timeless yet so human relation between nature and architecture.